If You Give a Dev a DAG

To increase the expressiveness of your API, let users write arbitrary programs.

If You Give a Dev a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG)…

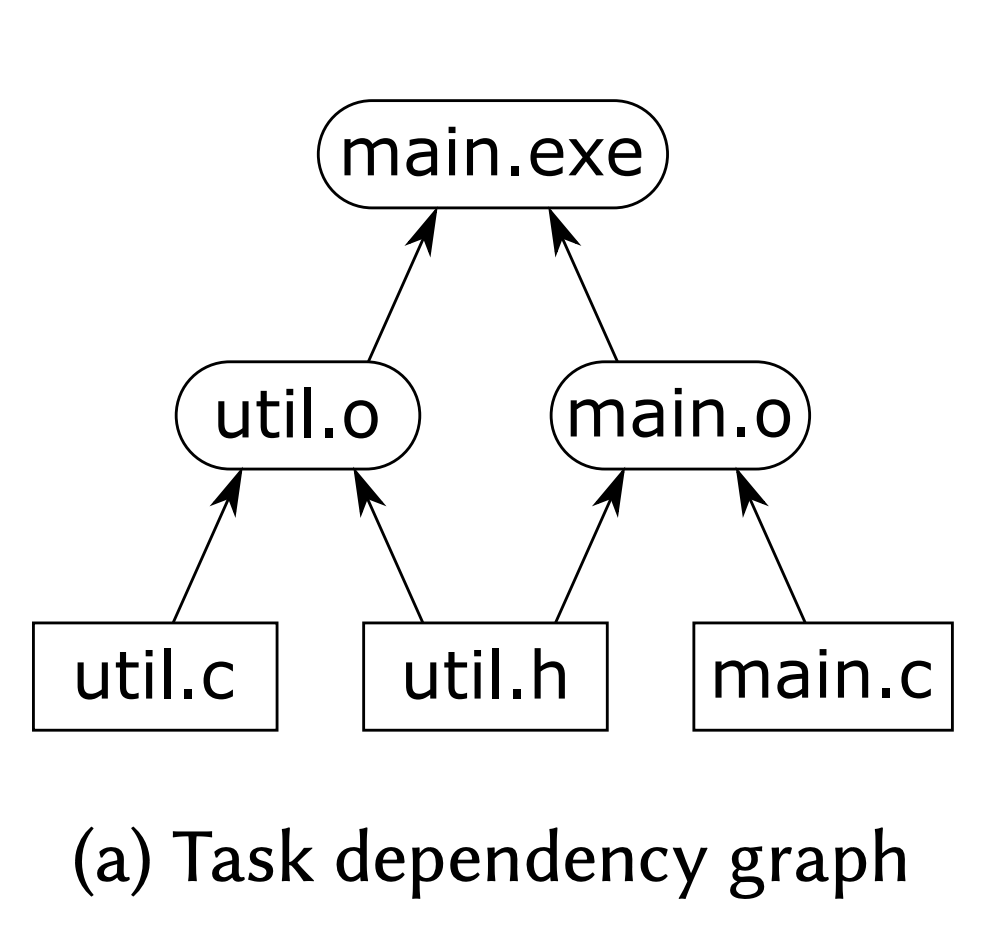

(left) neural network DAG from Wikipedia, (right) task DAG from “Build Systems à la Carte”

When designing a new API for some specialized kind of programming (e.g. machine learning or build systems), we often start modeling the domain using a directed acyclic graph (DAG). I can think of a few reasons for this. (There are probably more.)

- We typically start by identifying the key primitives of our domain (fully connected layers, convolutions, etc. or tasks/files/modules), and then add straightfoward ways to compose them. This naturally yields a list, tree, or DAG structure.

- DAGs are very easy and intuitive to draw. They tend to match the diagrams we use to model these domains, and its fairly easy to make UIs for constructing DAGs.

- Compared to the structures we’ll see later, DAGs are very easy to reason about. Just flow your information through the edges of the graph. Split them when there are multiple out-edges. Combine them when there are multiple in-edges.

This approach tends to work well for a little while, but if you give a dev a DAG…

They Will Ask You for Control Flow

Soon enough you start getting GitHub issues for edge cases. Maybe someone’s build dependencies depend on the contents of a file or runtime information. Maybe someone’s file imports depend on their browser version, or whether they’re running in development or production. Maybe someone wants to write a recursive neural network (RNN).

How do we modify our DAG to support these?

Hide the control flow in a box. If we add a custom operator, say RNN, to our graph, then we

can hide all of our dynamism inside a node in the DAG. Problem solved! Well… until one of our

users comes along with a different dynamic use case. We’ll have to add that one, too!

Maybe we give them a way to write their own arbitrary nodes. But inside those nodes, they can’t use our beautiful graph structure. Hopefully there aren’t too many use cases for this pesky control flow stuff…

Add some control flow operators. If we get a lot of requests for graphs that need control flow,

we might then choose to add some actual control flow constructs to our graph. Typically something

like if or while (think TensorFlow’s while_loop or Vega-Lite’s condition). This works a lot

better! You can handle more people’s use cases without adding new operators.

A limited set of control flow operators works until someone wants to write a new custom control flow

block, maybe they want a switch or a map? Sure, they could write these using if and while,

but they want to wrap that code into a new box so they can use some higher-level operators.

So if you give a dev control flow…

They Will Ask for Functions and Macros

“Ok!” you say, “Let’s add support for function definitions. That way people can write their own control flow operators. We’ll even give them macros! Sure, they’re complicated, but sometimes people want to write really funky semantics. Let’s give it to them.”

You see where this is going, right? This is Greenspun’s tenth rule in action. By repeatedly trying to support more use cases without getting overwhelmed by feature requests, we have stumbled our way into writing a general-purpose programming language!

So What Do We Do?

Here are a few options that provide different tradeoffs between how much of a user’s program we can represent and how difficult it is to implement our API.

Tough it out. Make a limited, ad-hoc language and live with the consequences. To be honest, this works fairly well in some cases. The reason is that as you get more expressive, the number of use cases goes down and the level of expertise required to use these advanced features goes up. So you might end up hitting diminishing returns as you increase the expressiveness of your language.

Embed yourself in a general purpose language. Instead of implementing features like control flow and functions yourself, you can design your API to take advantage of your host language’s implementations of these! This is how PyTorch and ggplot2 work, for example. This both gives you a lot of expressiveness, and also allows your users to work with constructs from the host language they’re already familiar with. A PyTorch user can look at Python documentation to figure out how loops work, which greatly reduces the documentation and maintenance burden for you.

On the other hand, leveraging the host language makes it harder to reason about those features yourself, since they’re now opaque to your system. You can get around this with custom static analyzers (e.g. React’s rules-of-hooks linter) or try to compile the host language yourself (e.g. you can write a Python decorator that lets you grab, inspect, and modify all the source code in the function it decorates). However, these approaches require lots of extra work, and you have to deal with all the quirky features of your host language (e.g. Python scoping rules).

Extend a general purpose language. You can “extend” your host language with macros (if you’re fortunate enough to work in a language with macros). Macros come with their own tradeoffs, especially for debugging.

Another approach that’s been popular recently in the JavaScript ecosystem is to write compiled extensions to the host language. These range from React’s macro-esque JSX syntax to Solid’s compiler to Svelte’s even more sophisticated reactive computation model. TypeScript also falls into this bucket. This is a nice sweet-spot between a typical embedded approach and the one we’ll look at next, but it still requires a lot of fiddling like the embedded approaches do. You also might need to write a custom parser and/or typechecker.

Full send! Write your own programming language. The most intensive approach you can try is to build your own programming language. The advantage of this approach is you have complete control over the semantics of your language, which is useful for implementing something like Rust’s borrow checker and expressive type system. On the other hand, to do this well typically requires a large team, because you will have to build and maintain a parser, typechecker, and compiler not to mention a language server and documentation. This is all on top of solving the domain-specific problems you originally wanted to address!

You can only really pull this off if you have a big team, and even then you will have to make lots of little language feature decisions that can distract you from your original goal.

See Also

For some more commentary on these issues, check out the related work section of the paper I co-authored in 2019 on programming languages for deep learning, “Relay: A High-Level Compiler for Deep Learning.” There’s also this great substack on a tower of language expressiveness similar to the one I talked about in this post: https://subconscious.substack.com/p/a-kardashev-scale-for-interfaces