Searching for My Next Scenius

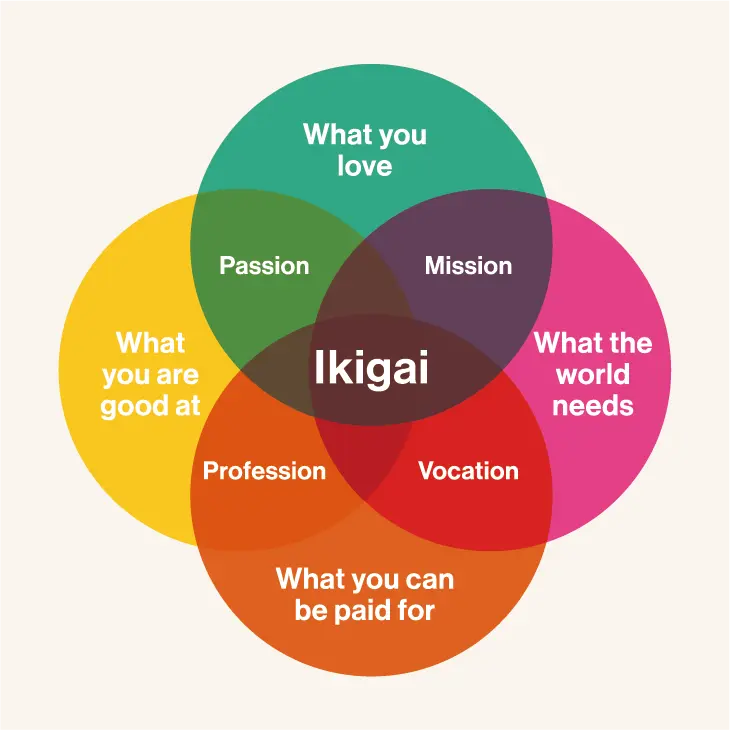

The notion of ikigai as criteria for leading a rich and fulfilling life is very popular these days.

But I think it’s missing one crucial element: community. If you peer closely at any heroic effort of a single person, you will find a whole team or community in which they did that work. Musician Brian Eno dubbed the intelligence of this broader group of people a collective “scenius.”

Kevin Kelly identified four qualities of a scenius that contribute to its power:

- Mutual appreciation — Risky moves are applauded by the group, subtlety is appreciated, and friendly competition goads the shy. Scenius can be thought of as the best of peer pressure.

- Rapid exchange of tools and techniques — As soon as something is invented, it is flaunted and then shared. Ideas flow quickly because they are flowing inside a common language and sensibility.

- Network effects of success — When a record is broken, a hit happens, or breakthrough erupts, the success is claimed by the entire scene. This empowers the scene to further success.

- Local tolerance for the novelties — The local “outside” does not push back too hard against the transgressions of the scene. The renegades and mavericks are protected by this buffer zone.

Sceniuses can exist at many scales, from a handful of people to many thousands. I have been fortunate enough to be a part of or have been adjacent to several sceniuses. But since COVID I have struggled to find new ones that feel like home.

K-12

In K-12 the Bay Area was really good at fostering sceniuses. The math kids would go to the same math competitions, the same math circles, the same math camps. The jazz kids would go to the same festivals, join the same bands, and attend the same jazz camps. In both instances, this sheer volume and frequency of opportunities to bring like-minded people together emboldened communities of passionate people that were able to accomplish pretty remarkable things for their age.

At a smaller scale, I was involved in First Tech Challenge in high school. My team was made up of friends who all went to the same school. We hung out during school and afterwards for hours at a time. Again it was through the volume and frequency of opportunities to connect that we were able to form a tight intellectual bond. We always knew who contributed what to the team, but we celebrated our successes and suffered our losses collectively. We placed 2nd in the world our senior year.

College

In college, I stumbled into the University of Washington’s Programming Languages and Software Engineering (PLSE) lab. This macro-scenius contained within it several smaller sceniuses such as the teams around TVM and egg. Before the egg project, e-graphs weren’t well known in the broader research community. However, within the PLSE scenius, e-graphs had already been used in projects like Herbie and early versions of Szalinski. Once Max Willsey developed the first versions of egg, however, e-graphs quickly saturated the scene, making its way into an updated Herbie, and the published versions of Szalinski and SPORES. It’s probably better to look at these projects as proxies for the people behind them: Pavel Panchekha, Chandra Nandi, and Remy Wang, respectively. All three and Max were part of the PLSE scenius at the same time, and all of them contributed (and continue to contribute) their unique perspectives to the development of egg.

Egg was able to spread quickly in part because of the tight-knit nature of PLSE. As with other sceniuses, PLSE fostered a high volume and frequency of opportunities to connect. PLSE provides a shared lab space (including Max’s permanent desk at the time) where people frequently talk about their individual projects. The group offers weekly lunches (where students frequently present) and reading groups. Students typically go out for lunch multiple times a week, attend TGIF events on Fridays, and go to the local pub. As a result, project collaborations form naturally and it’s common for PLSE papers to have 5-8 co-authors including three grad students.

Post-COVID

Post-COVID, finding or cultivating a scenius has been much more difficult. At MIT, at least post-COVID, the research groups around me are fractured such that a scenius is hard to form. There are few shared spaces or regular get-togethers, especially ones that transcend advisor boundaries. (The systems and theory groups are possible exceptions to this.)

And while there are dozens of researchers working in the areas I’ve gravitated towards, PL-HCI and diagramming, there is no clear scenius in either, or at least none that I consider to be home. While there are shared events like the PLATEAU workshop, there is no clear home research community for either field. Instead, PL-HCI is smeared across PL and HCI venues like SPLASH and UIST. Diagramming is similarly distributed among SIGGRAPH, VIS, and CHI. Both are, for now, on the fringes of other research communities.

On paper, diagramming satisfies the ikigai criteria for me.

- Do I love it? I’d say so. Diagramming occupies my mind most of the time these days.

- Am I good at it? My PL background and the sheer amount of time I’ve spent marinating in the area give me a unique, valuable perspective.

- Can I be paid for it? If a PhD salary counts, then yeah.

- Does the world need it? Tools like Figma, PowerPoint, and Brilliant’s Diagrammar would suggest that there is a real need for diagramming tools.

Yet I feel that without access to a proper scenius, I cannot do my best work. I’m still searching.